I wanted to eat the air. I think that's a first for me.

Art, propaganda, and history: Visiting the Bayeux Tapestry

Turning into the courtyard of the Bayeux Museum, my first impression was not of the 17th-century façade or the neatly-manicured path, but of these banners, rather shamelessly harnessing the advertising power of the HBO television phenomenon, Game of Thrones.

I am often annoyed by facile pop culture references aimed at “selling” history or historic sites to the (presumably indifferent) public. But this didn’t bother me. For one thing, it was fitting, and thus actually funny, and for another, the Bayeux Tapestry has been exploited by so many groups for personal, and sometimes sinister, gain, that it was nice to see the tapestry exploiting somebody else’s notoriety for a change.

The Bayeux Tapestry tells the story of how, in 1066, Duke William of Normandy launched a successful invasion of Anglo-Saxon England and thus got to go down in history as “William the Conqueror.” The plot, in a nutshell, is as follows: England’s aging king, Edward (“the Confessor”) sends a trusted nobleman, Harold Godwinson, to Normandy to assure William of his position as Edward’s heir, but when Edward dies, Harold is offered the crown by the governing council and treacherously takes it for himself.

Harold, right, confirming Edward’s offer of the throne. To be safe, William makes him swear allegiance. Only after Harold does so, does William reveal that Harold had actually sworn upon a sacred relic. The tapestry’s point is that Harold’s usurpation is an offense against God as well as against William. {PD-US via Wikimedia Commons}

Brimming with righteous rage, William assembles a huge invasion force (the construction and loading of the ships is depicted marvelously in the tapestry) and, on October 14, 1066, defeats Harold at the Battle of Hastings—one of the longest battles in medieval history.

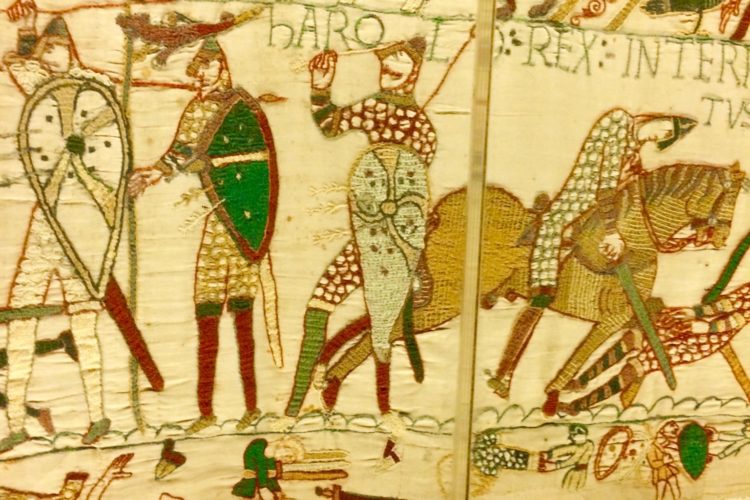

Norman knights charging uphill toward the Anglo-Saxons. Only the Normans fought mounted. The Anglo-Saxons fought on foot–and wielded two-headed axes. {PD-US via Wikimedia Commons}

But, of course, that isn’t the whole story at all. The Bayeux Tapestry is a perfect example of how it really pays to know the history behind a work of art. Don’t mistake the tapestry for a straightforward embroidered encyclopedia entry, it’s a piece of straight up Norman propaganda. Produced at a time when William’s hold on the English throne was in doubt, it was aimed at reconciling the resentful English to his rule. (For some context, this is the same William who built the Tower of London and Windsor Castle, among many other castles, and for much the same reason: to make clear to the English who was in charge now.)

A 210-foot-long linen panel, skillfully embroidered with expensive and high-quality silks and wools, the tapestry actually isn’t a tapestry at all. But the misleading name is apt, because when it comes to the “tapestry,” contradictions abound. It’s an unapologetically propagandistic account justifying William’s conquest, but it paints his foe, Harold, in an oddly sympathetic light. It’s also an important piece of the French cultural heritage and major vessel of regional and national pride, but it was most likely constructed by English women, with English materials, in England.

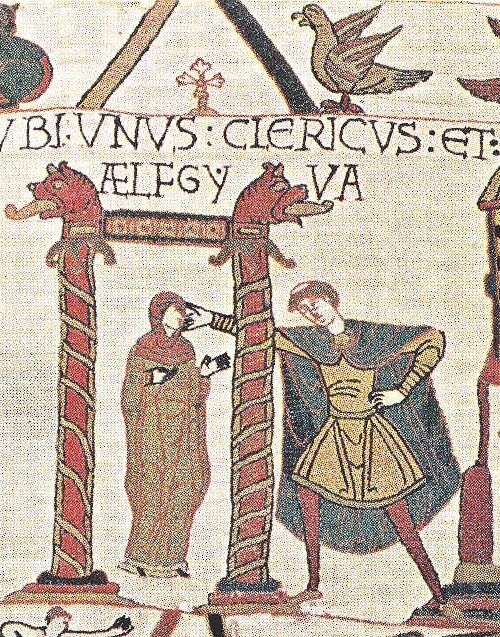

If you look closely, you can see the worn linen of the “tapestry’s” background. The identity of the woman on the left has never been established. {PD-US via Wikimedia Commons}

Nor is the actual tapestry the whole story. Over the centuries, it has been deployed in the service of both French and English propaganda. During World War II, it even caught the fancy of Nazi leaders, who tried to appropriate its meaning to suit their own sinister purposes.

A Mysterious Patron…

In the Middle Ages, grandiose works like this didn’t just happen. They were commissioned by wealthy patrons, usually with a purpose in mind. Scholars agree that the tapestry was commissioned to flatter William and, more broadly, to bolster Norman rule in England. The candidate these scholars put forth is usually William’s brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux. Odo benefitted greatly from the conquest (William made him the Earl of Kent) and would have had every reason to publicly defend its legitimacy.

Odo in one of his four appearances in the tapestry. {PD-US via Wikimedia Commons}

Odo’s prominent placement in the tapestry (he features in four separate scenes) is also telling; artists commonly flattered their patrons by emphasizing their importance. Also, the tapestry did wind up in Bayeux, the seat of Odo’s bishopric (the assumption is that he bequeathed it to the cathedral on his death).

Bayeux Cathedral in 2015.

But, in The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece, the late art historian Carola Hicks makes the intriguing case that the guiding force behind the tapestry wasn’t Odo at all, but Edith Godwinson, sister of Harold and widow of King Edward the Confessor.

In an awkward position after the Conquest, Edith would have been angling for power and influence in the new regime. A noted patron of the arts, she also would have had the necessary connections to commission such an ambitious project. Edith as “author” would go far toward resolving one of the oldest questions about the tapestry, why Harold, who is by default the story’s “bad guy,” is portrayed more as a tragic and misguided hero than a villainous usurper.

Edith, most likely at her marriage to King Edward, as shown in an unattributed Cambridge University manuscript. {PD-Art via Wikimedia Commons}

Hicks contends that Edith would have seen it in her own interest to flatter William and promote English acceptance of Norman rule, while at the same time wishing to discreetly honor her fallen brother. Though Hicks doesn’t discuss this part, I have read elsewhere that the Godwinsons were an unusually close family, so Edith’s devotion certainly rings true. (Of course, the youngest Godwinson brother, Tostig, did lead a rebellion against Harold, and then died in the fighting. But, I mean, every family has problems.)

It’s tempting to ask, “so what?” The general intent behind the tapestry–Norman propaganda–is clear, so does it really matter (to anybody other than those nitpicky historians) who commissioned it? Yes, because the tapestry isn’t a sterile piece of art. It’s a key document of Anglo-Norman history and a beloved artifact of Norman-French heritage. Assigning authorship to the English Edith over the Norman Odo is a big deal.

As far as I can tell, Hicks’ theory has found few takers. Most scholars continue to bet on Odo. This must comfort those who are committed to maintaining the tapestry’s “French connection,” because while the tapestry may have been “conceived” in France, it almost certainly wasn’t “born” there. The consensus among leading scholars is that the tapestry was likely stitched by English women embroiderers, who were known throughout Europe for their skill and whose style and quality matches the tapestry’s.

Odo, as Earl of Kent, would have had access to the embroidery workshops of Canterbury (though Edith, as a patroness of the wealthy Wilton Abbey, would also have had access to noted needle-working communities), and if the tapestry was embroidered in English style and meant to convince English viewers of the legitimacy of William’s rule, it makes a lot of sense that it would have been created and initially displayed in England. Interestingly, the Bayeux Museum’s website is silent on the matter of the Tapestry’s origins.

The tapestry was stored in Bayeux’s Cathedral for centuries, only being taken out once a year, until antiquarians “discovered” it in the 1600s. It has featured prominently in Anglo-French military conflicts, cultural clashes, and national mood swings ever since, with both sides laying claim to the tapestry’s origins and legacy. In the early 1800s, Napoleon put the tapestry on display in Paris, a move meant to foster national pride as well as remind the English that (Norman) French warriors had conquered England once and could do it again.

Though the tapestry has long since been moved to its own museum, its home for centuries, Bayeux Cathedral, is well worth seeing. The whole thing is lovely, but I’m a sucker for stained glass.

English representations of the tapestry have been diverse, but tend to track with however mainstream opinion feels about France or continental Europe at any given moment. For much of the 18th and 19th centuries—times of frequent conflict with France as well as fervent interest in the origins of the English constitution—opinion looked favorably on the Anglo-Saxon Harold, considering his reign an era of lost English liberty and castigating the Norman-French William for ushering in centuries of continental-style tyranny.

But in the 20th century, with the experience of both world wars, public favor shifted to William and away from the Anglo-Saxon (and thus Germanic) Harold. While I haven’t found anything yet, I am willing to bet that in some corner of the internet, there is a Brexit-inspired take on the tapestry, no doubt bewailing the moment the European yoke was imposed on England.

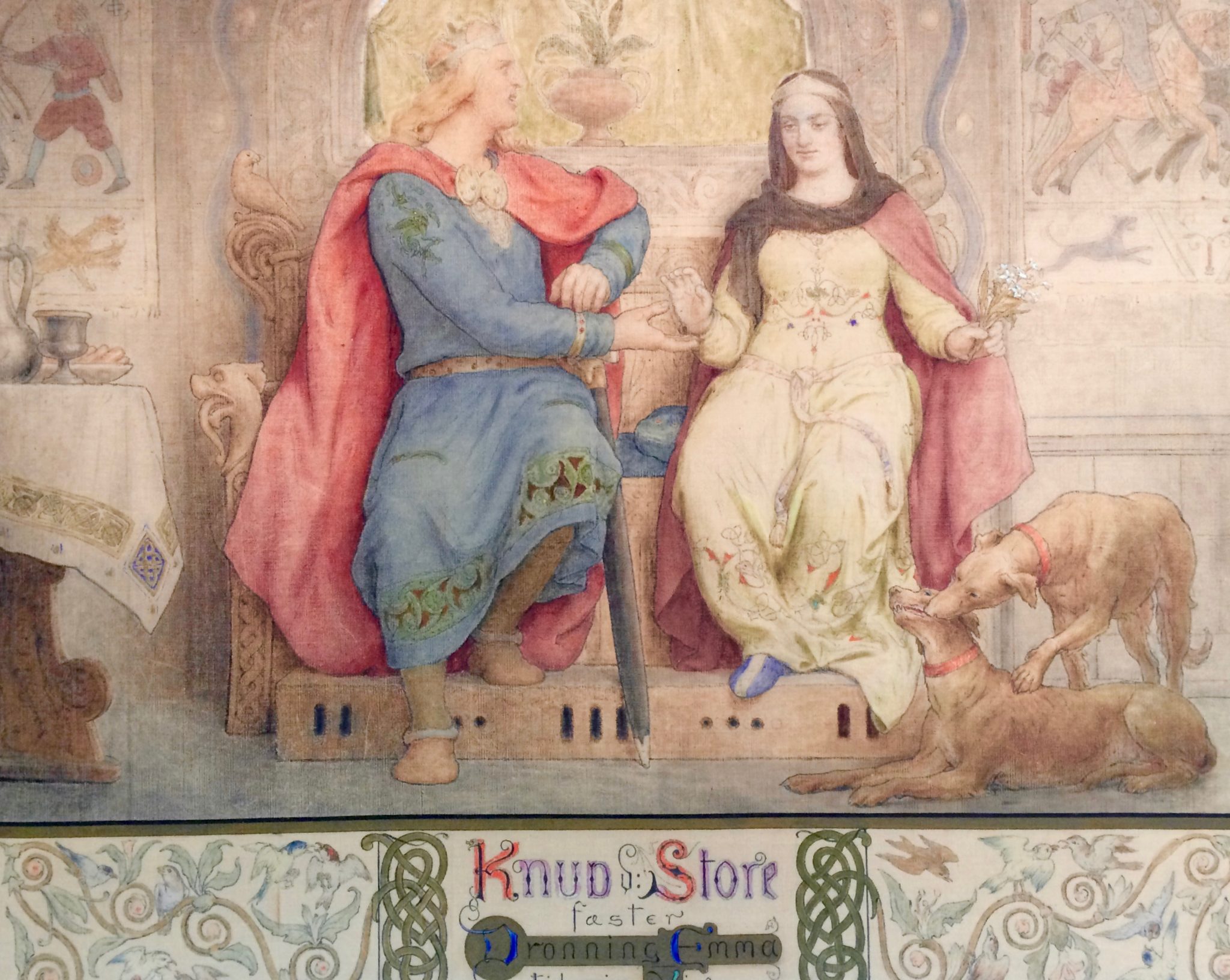

Interest went beyond France or England. In the late 1800s, a Danish artist painted a series of frescos at Frederiksborg Castle depicting the Danish conquest of England and clearly meant to evoke the tapestry. But to me the strangest, and most disturbing, of all the meanings imposed on the tapestry was the one developed by the Nazis. Interest in the tapestry among high-ranking Nazis apparently dates to the 1930s, but took on greater urgency in 1940, with the fall of France and the Germans’ ultimately-failed attempt to invade Great Britain.

A scene from the “Danish Bayeux Tapestry,” a series of frescos depicting the Danish conquest of England in 1015-16. Frederiksborg Castle, Denmark.

As Napoleon had before him, Hitler recognized the propaganda value of the tapestry, especially its implied reminder to the British that the English Channel had not always protected them. But the Nazis had their own special twist; they wanted to claim the tapestry as a work of Aryan art and the story of a Germanic (and thus “Aryan”) victory. By emphasizing the Viking origins of the Normans (the name was a reference to the “North men” who had conquered large swaths of northern France a few centuries before the Conquest), the Nazis recast William as a German leader, in Hicks’ words, a “prototype Führer.” There may even have been a plan to remove the tapestry from France and place it in Hitler’s (never-realized) Führermuseum.

The layout of the Bayeux Museum encourages visitors to make quick work of the tapestry. The included audio guide contains 20 minutes of fast-paced narration and the narrow design of the tapestry room makes it hard to linger without holding up traffic (but if you wait for the guards to look away, it’s possible to get to the end and then retrace your steps, permitting a second walk-through. Just sayin’…..).

Visitors are not encouraged to linger in the tapestry room, but, when at the ticket desk, you can spend all the time you want with this random diorama of William and his horse.

Lastly, photography is not permitted in the tapestry gallery (which is why the above photos of it come from the internet), but I saw plenty of phones out. The gallery is kept in near darkness to protect the tapestry. The only illumination comes from the weak lighting inside the case, so it’s hard for the guards to really keep an eye on this. I decline to comment on where this photo, of Harold fatally stricken with an arrow to the eye, might have come from…

I can’t explain it, but somehow this image of Harold just appeared on my phone! Weird.

Have you seen the Bayeux Tapestry? What did you think? Have you found that knowing the background of what you’re seeing enhances the experience?

This is a brilliant study of an example of how one artifact can be interpreted in many different ways, not only by the curators of the museum but also by later historical actors, down to the Nazis. Remembering that Shakespeare mentioned Edward the Confessor in Macbeth, I tried to consider how (or if) the problematic succession to Edward and the Norman conquest related to events in Scotland at the time but my head started to hurt so instead I’ll quote Shakespeare and ask if you have an idea about why Shakespeare wrote this–it might not be familiar because this section of the play is removed in just about every production of Macbeth because it just seems so out of place. Why did he put it there?

A most miraculous work in this good King,

Which often since my here-remain in England

I have seen him do. How he solicits heaven,

Himself best knows: but strangely-visited people,

All swoll’n and ulcerous, pitiful to the eye,

The mere despair of surgery, he cures,

Hanging a golden stamp about their necks,

Put on with holy prayers: and ’tis spoken,

To the succeeding royalty he leaves

The healing benediction. With this strange virtue

He hath a heavenly gift of prophecy,

And sundry blessings hang about his throne

That speak him full of grace.

(IV.iii.147-159)