I wanted to eat the air. I think that's a first for me.

Madrid’s Other Must-See Museum

When in Madrid, if you like history or art, even a little bit, or are a person who prioritizes seeing the “major” sites in any new place, it goes without saying that a visit to Madrid’s “Golden Triangle” of art museums is in order. A stroll through the Prado or the Reina Sofia is a lesson in Spanish history just as much as an experience of Spanish art. The jewel-like Thyssen-Bornemisza packs a smaller but dazzling punch with its eight-century romp through European art. And, since you’re in the neighborhood, there’s the immense Palacio Real de Madrid (Royal Palace of Madrid) as well. (I would be remiss in my royalty nerdiness if I didn’t at least mention that!)

After a couple (or more) days feasting on these delights, even the most devoted museum-goer might be ready to wile away the rest of her visit with a tapas crawl and, if feeling ambitious, a stroll around El Retiro park. But, please, hang in a little while longer. Madrid has another must-see museum!

You don’t want to miss this cool marble sarcophagus, do you? Imported from Rome in the 3rd century C.E. (in other words, by somebody with a lot of money) and decorated with both Old and New Testament scenes, it spent centuries in the Cathedral of Astorga in León.

The Museo Arqueologico Nacional (or MAN) was founded in 1867 by Queen Isabel II and, despite its name, contains much more than archeological artifacts (cool though those are).

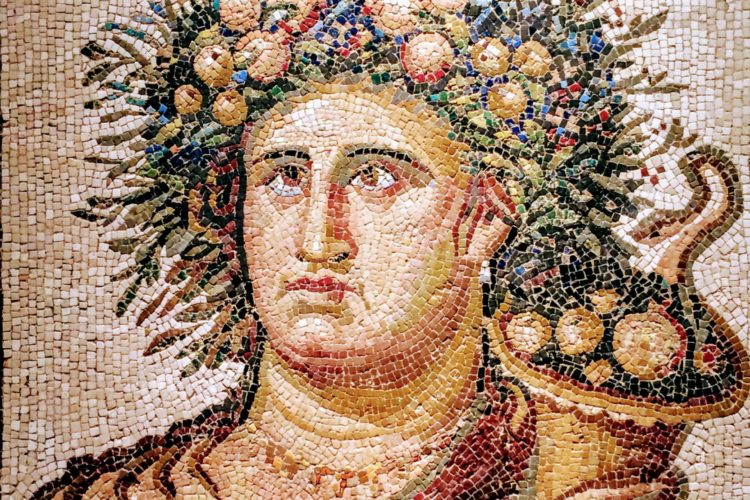

Spanning from prehistory to the nineteenth century, the museum tells Spain’s story through a material culture lens. Bronze Age goldwork, Roman mosaics, Visigothic eagle badges, jewelry from Al-Andalus, 17th century furniture, Scientific Revolution-era instruments–they’re all here and so is a whole lot more. If it had a physical existence on the Spanish side of the Iberian peninsula, happened to survive the haphazards of time, and isn’t a painting, it’s probably here. That is my kind of magpie museum curation.

These marble statues of Livia, the consort of the emperor Augustus, and her son, the emperor Tiberius, were found together in the ruins of the Roman city of Paestum (southern Italy) and date from the very early 1st century C.E. If you’re a fan of I, Claudius, you might share my surprise at how harmless they look…

The enormous collection could easily be overwhelming, but the MAN is so well-designed that it is possible to take in a whole lot with ease. The museum reopened in 2014 after a six-year refurbishment and they did a great job. Every item is well-signed, with detailed descriptions in Castilian and English (I noticed numerous signs in braille as well). There is an excellent audio guide, with subtitles, available for 2€ and free to visitors with hearing or visual impairments. The guide is also available for download and I had no trouble playing it on my iPhone.

Wooden scrollwork from the 14th or 15th century, decorated in the hybrid Mudéjar style. One of the most interesting things I learned about medieval Spanish culture is that, as the Christians gradually took back the peninsula from the Muslims, they were often captivated by Islamic art and architecture. Eventually a hybrid style, mixing conventional medieval Christian design with Islamic motifs, emerged.

The collections are for the most part arranged chronologically. Many pieces, such as this statue of Pedro I, are displayed on open daises, which allow the visitor to get a thorough look. The curation does a great job equipping the visitor with just enough helpful contextual information.

Exhibits covering the collapse of Roman Hispania are especially well-handled. Sizable but unobtrusive interactive maps covering major political transitions, such as the decline of Rome and the rise of the Visigothic Kingdom and later Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) are well-thought out and help a great deal.

Statue of Pedro I, King of Castile, at prayer. Pedro’s joint nicknames, el Cruel and el Justo, hint at a decidedly mixed reputation. But Geoffrey Chaucer, whose patron, the Duke of Lancaster, fought side by side with Pedro, seems to have liked him, lamenting his death (O worthy PETRO, glorie of SPAYNE) in The Monk’s Tale.

Most rooms are large and airy, with a great deal of natural light. Even in those rooms where the lights are dimmed to protect the artifacts, the floor plans are so spacious and the number of displays kept limited, that you don’t go into sensory overload.

One of the highlights of the collection is the votive crown of King Recceswinth, a seventh-century ruler of Visigoth Spain. Commissioned by Recceswinth as an offering to the Church, it was an emblem of piety rather than something to be worn. The dangling gold letters read, “[R]ECCESVINTHVS REX OFFERET,” or “King Recceswinth offers this.”

The Visigoths get about three sentences in most textbooks, filed away as one of the several semi-pagan, barbarian hordes that abruptly overthew the Roman empire. But, in reality, the Visigoth kingdom was part of a slow process by which the classical Roman world slowly evolved into the early Middle Ages. Recceswith’s crown provides a great window into this.

Recceswinth’s votive crown, with a bonus image of me, and the random guy behind me, in the reflection.

Originally followers of Arianism (a non-trinitarian form of Christianity), the Visigoth conquerors embraced the western (Roman Catholic) Christianity of their subjects. This was meant to forge politically-expedient links with the church in still-influential Rome. The crown’s magnificent sapphires came originally from Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) and testify to the still-robust trade networks of the late classical and early medieval worlds.

If the crown’s design looks Byzantine to you, that’s because it essentially is. While goldsmiths employed Germanic metalworking skills, the design draws on elements from the eastern Mediterranean. Recceswinth was a great admirer of the Byzantine (eastern Roman) empire and modeled many of his cultural and legal reforms on it. These were moves to cast the kingdom as a descendant of the Roman world, not a foreign replacement. The votive crown, meant for display, would have helped communicate this in a largely illiterate world.

Embracing aspects of Mediterranean culture did not mean that the Visigoths entirely abandoned their own Germanic ways. One example is that they continued to wear the tunic and trousers once mocked by the Romans. Eagles were a common motif in Gothic cultures, and brooches such as these would have been used to secure capes or keep tunics closed.

The crown, along with about 25 other pieces of goldwork, was discovered in 1858 after a fierce storm washed away a graveyard near Toledo. The Visigoth kingdom fell to advancing Arab Muslim forces in the early 8th century, and the gold was probably buried there for safekeeping.

After its discovery, the treasure was acquired by the French government, which housed it in the Cluny Museum (now the Musée National du Moyen Âge). It wasn’t until 1943 that half the collection returned to Spain. This deal was the result of delicate negotiations between Franco’s fascist regime and the Nazi puppet state of Vichy France–a bit of trivia that, perhaps not surprisingly, goes unmentioned in the museum’s signage.

I spent about 2.5 hours at the MAN and could have easily spent hours more. I didn’t even make it past the Middle Ages. I only left when I did because I went on a Sunday when the museum has limited hours. I will definitely prioritize a return visit!

How to get there

The MAN is easily accessible via public transport, with two nearby metro lines, Serrano (Line 4) and Retiro (Line 2), and a bus stop right outside. See the official website http://www.man.es/man/en/ for more information.

If you can’t make it in person, the MAN has recently partnered with Google to display high resolution images, accompanied by brief descriptions, of about 100 of its artifacts.

https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/u/0/partner/museo-arqueologico-nacional

And if you’d like to know more about the Visigoths (and, really, who doesn’t?), two good places to start are:

- The Visigoths, from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: An Ethnographic History, edited by Peter Heather, 1999.

- Christopher Howse, A Pilgrim in Spain, 2011.

Have you been to the MAN? How do you think it compares to Madrid’s other museums?

“If you’re a fan of I, Claudius, you might share my surprise at how harmless they look…”

I think I spotted a typo–did you mean to write “how ARMLESS they look”?

OK, sorry, that was terrible. But more seriously, I wonder if the harmless appearance corresponds more to the reality–or at least the contemporary perception–of these two than the TV show? From what I know (and I haven’t read the books) Graves pulled the most salacious details from Suetonius and other sources to put together his deliciously evil portrayal of the wicked empress.

Hmmm…I wonder if the lower part of Livia’s body signifies the eventual de-feet of the Empire….

I’m so sorry; that was worse than the “arm” “joke”. And more importantly, it’s incorrect, as you point out–most of us think the Empire was defeated by some sort of Goth band (The Cure? Joy Division?) whereas it was “a slow process by which the classical Roman world slowly evolved into the early Middle Ages”.

I hope you were able to go back later and see more!