I wanted to eat the air. I think that's a first for me.

“Appalling” and “Totalitarian:” Oslo’s Must-See Gustav Vigeland Sculpture Park

Because, for once, I didn’t do my history homework, I wandered into the Gustav Vigeland Installation at Oslo’s Frogner Park unaware that I was doing anything other than paying a visit to a sculpture park. Of the charged emotions provoked by his work, or the nerve he himself touches among Norwegians, I was completely unaware.

What the heck am I talking about, do I hear you ask? To back up a bit, the Gustav Vigeland Installation (or, more simply, the Vigeland sculpture park) is one of the largest sculpture parks in the world, and the largest by a single artist. It is also one of Oslo’s top visitor attraction, which is hardly surprising, as it’s a stunningly beautiful landscaped park strewn with a lot of, err….attention-getting sculptures.

The view upon entering Oslo’s Frogner Park.

Gustav Vigeland was undoubtedly Norway’s greatest sculptor and one of its finest twentieth century artists. He seems to have been something of a prodigy, working with leading sculptors and receiving commissions at a fairly young age. He won a number of state and private grants to travel abroad and was much influenced, at least in his early years, by the works of Auguste Rodin.

Many of his commissions came from the Norwegian government, which was spending up a storm on public works and public art in the first decades of the twentieth century. Norway had only obtained its independence from Sweden in 1905 and the government felt strongly that its capital should be both suitably grand and suitably Norwegian. With this in mind, the capital, which had been called Christiania for several centuries, reverted to its old Norse name, Oslo.

Vigeland benefitted from this expansionist vision for most of his career, but at no time so greatly (and so dramatically) as in 1921. In what can only be described as a very sweet deal, Vigeland was granted a state-subsidized (and fully-equipped) studio and luxury apartment. In exchange, he promised to donate all of his future work (save private commissions) to the state.

The grandest result of this deal can be seen at Frogner Park, which was itself redeveloped around this same time from marshland into a public park by the same building-minded city authorities. Eventually the two projects sort of grew up together, with the designers of each taking into consideration–at least a little bit–the plans of the other. Today Frogner features more than 200 sculptures in bronze or granite.

Undeniably strange sculpture not your cup of tea? It’s okay. Frogner Park is full of gorgeous areas this like one.

Entering the park is a little like entering the palatial gardens at Versailles, Drottningholm, or even the slightly less elaborate Frederiksborg Castle–another clue that these public projects were part of a larger plan to enhance and beautify Oslo. A series of tree-lined avenues leads visitors deeper into the park until they reach a large stone terrace. From here, visitors can look straight ahead for a wide-angle view of the park’s focus point and most famous piece of sculpture, Vigeland’s “Monolith.” If rolling hills dotted by ponds are more to your taste, there are plenty to be seen from either side.

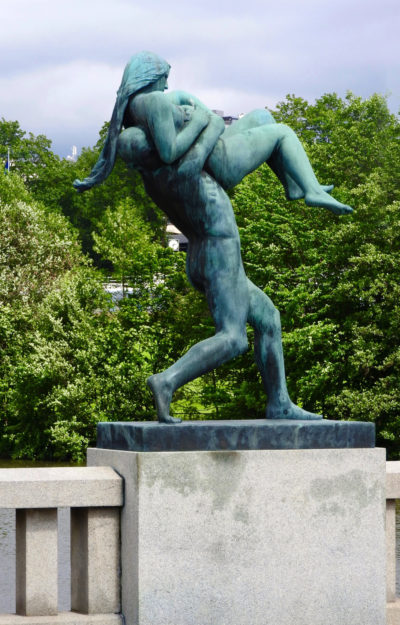

Accompanying visitors every step of the way are Vigeland’s sculptures of men, women, and children in various moods and poses. There’s a real sense of whimsy and even some humor in these early encounters–such as the famous tantrum-throwing toddler–though the sculpture showing a man picking up a woman from behind and seemingly preparing to throw her, javelin-style, into the unknown, is a bit unnerving. I would advise taking this moment to smile at the sculpted figures and their antics; as you approach the monolith, the sculptures get darker.

The enigmatic Vigeland only named his sculptures–when he named them at all–with stark descriptors such as “Angry Boy” and “Man facing Lizard.” Critics have taken this both as an invitation from the artist to imbue his works with our own meanings, or as evidence of Vigeland’s essential coldness and indifference to individuality and humanity.

“Angry Baby” is one ticked off little kid! (By the way, I think Frogner Park would be a great place to take kids. I can’t imagine that they wouldn’t be intrigued by the sheer weirdness around them and not have a million questions.)

I am not an art historian (though that usually doesn’t stop me from opining on art…), but Vigeland’s work strikes me as chilling and more than a little weird, but not devoid of humanity. All the same, Vigeland was a famously unpleasant man and, looking at his work, I found that very easy to believe. Like that friend of yours who is definitely funny, but whose humor is always a little mean, Vigeland’s work beguiles, but doesn’t seem to be inviting you on a very pleasant ride.

The approach to the Monolith is surrounded on four sides by these elaborate iron gates. They’re for show rather than security (there are big open gaps between them), but I think they’re really cool.

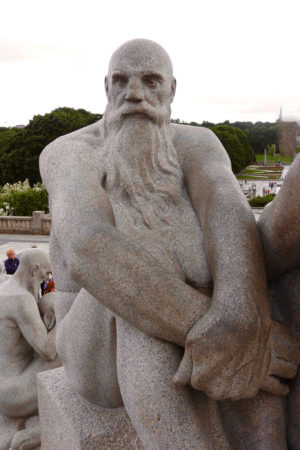

Reaching the center of the park, visitors are confronted with high stone steps, atop which sits the showpiece, the Monolith. Keeping the Monolith company are numerous granite figures of human beings at all stages of life. Like the others, the figures are all nude (save for the occasional bandana or scarf thoughtfully provided by a visitor); and, like the others, they have provoked their share of interpretations.

The Monolith is the pinnacle, and most controversial part, of the entire installation. 14.2 meters (approximately 45.5 feet) high, it is carved entirely out of a single piece of stone (hence the name, “mono” one, and “lith,” stone). Vigeland completed it in 1943, only a year before his death. And no, I can’t even begin to tell you what it means.

Some critics see the monolith as a symbol of “striving upward,” and a representation of humanity’s continued progress. I hope they’re right, because their vision is much prettier than mine. When I look at this, frankly, what I see is chaos and death. The intertwined and stacked human figures call to mind nothing so much as the World War II photos and newsreel images of the piles of corpses of concentration camp victims, or the unearthing of any of the twentieth century’s all-too-numerous mass graves.

(By the way, comments like that are the reason that nobody likes to hang out with historians. Contrary to our reputation, we are not boring, just depressing as hell.)

While we are on the subject of World War II, most of the controversy surrounding Vigeland relates to his supposed Nazi, or at least fascist, sympathies. His work has been compared to that of Arno Breker, whose sculptures of the idealized human form emphasized physical perfection and lacked any individuality, and were intended to exalt Nazi doctrine and showcase the “superiority” of Aryan peoples.

Arno Breker’s Aryan superman in Die Partei. Some critics have compared Vigeland’s work with Breker’s. What do you think?

I don’t know enough about either Vigeland or Nazi art to form a firm opinion of this, but from what I have read, it does seem as though Vigeland, if not embracing the Nazis, perhaps didn’t mind them so much. Understandably, this is distasteful to most Norwegians, for whom World War II and the Nazi occupation have great national meaning. When Germany invaded in the spring of 1940, Norway, despite being vastly outnumbered, held out for nine weeks. Ordinary Norwegians fiercely resisted the collaborationist government that took eventually power, and the resistance movement occupies an honored place in the national memory.

Vigeland, on the other hand, invited Nazi officers to his studio, and commented that he was happy that the occupying forces found strolling in Frogner Park amidst his sculptures to be so pleasant a pastime. Behavior like this helps to explain why Norway’s greatest sculptor seems to command cool respect rather than warm admiration.

I don’t know. Certainly Vigeland’s later work doesn’t line up with Nazi ideals of physical perfection. And if there is something anonymous and vaguely totalitarian about the monolith, then the boxy, granite figures that surround it seem to me, if not individualistic, then for sure, eminently human. In fact, these sculptures, especially the ones featuring elderly men and women, were the only ones in the entire park that made any kind of positive emotional impact on me. If Vigeland’s work isn’t a celebration of the diversity of the human experience, it does seem to recognize, at least here, the complexities of the human spirit. But, as ever, Vigeland is sphinx-like on whether this is a good or bad thing.

Obviously Vigeland, the man as well as the work, provokes strong reactions. Just run a search for “Gustav Vigeland” or “Vigeland sculpture park” and you’ll run into a bunch of interesting adjectives; “appalling” and “totalitarian” are just a small sample of what the internet has to say about his work (other good ones are “misogynistic” and “deeply weird”).

Even now, I still can’t really say if I liked the sculpture installation, or if I was just awed by it. And yet I’m pretty sure that, should I find myself back in Oslo, I would make a point of revisiting it.

Getting to Frogner

Getting from the city center to Frogner Park is a breeze. Both the tram and the bus stop near the entrance, and the Oslo pass is good for all forms of public transport. You could take a taxi, but I wouldn’t bother. Taxis are expensive and, believe me, Oslo is already expensive enough.

In fact, that’s a real perk of visiting Frogner Park–it’s free! The nearby Vigeland Museum (about five minutes’ walk) does charge admission. I didn’t go in, so I don’t know if it’s worth it, but the website has details. An adult ticket is currently 80 NOK (about $10 US), but Oslo pass holders enter for free.

So what do you think of Vigeland and his work? Amazing? Moving? Cold? Creepy? Inquiring bloggers want to know!

[…] Quien esté interesado por la controversia sobre la obra de Vigeland, puede visitar la web Into (https://www.intomore.com/travel/the-hidden-homoerotics-of-oslos-vigeland-installation) o el blog Through History-Colored Glasses (https://www.historycoloredglasses.com/2017/05/httpswww-historycoloredglasses-com201705-oslos-must-se…). […]

When I visited Oslo about 25 years ago I took a bus to the Vigeland Sculpture Park two days in a row. I have never seen anything in the world more exciting and amazing even though I’ve seen wonderful sights in Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Italy, and others countries.

Hi Laurie,

Thanks for the comment I’m jealous that you went two days in a row. I only had two days in Oslo and I ran around the whole time, and still didn’t see everything I wanted to! I need to go back (both to Oslo and to the Sculpture Park), such an awesome place.

I was there today… and I need to go back there tomorrow. I found it truly awesome and inspirational. I started, in fact, in the museum of, largely, plaster models of the final sculptures and the models themselves were stunning. Seeing them out in the wonderful park (despite the rain!) only added to their brilliance.

[…] To finish it, I will quote yet another witness – a female travelling blogger.https://www.historycoloredglasses.com/2017/05/httpswww-historycoloredglasses-com201705-oslos-must-se… […]

[…] Quien esté interesado por la controversia sobre la obra de Vigeland, puede visitar la web Into (https://www.intomore.com/travel/the-hidden-homoerotics-of-oslos-vigeland-installation) o el blog Through History-Colored Glasses (https://www.historycoloredglasses.com/2017/05/httpswww-historycoloredglasses-com201705-oslos-must-se…). […]

Vigeland was not a Nazi, and he was apolitical in his art. Of his more than 200 extant letters, none of them discuss political themes or express admiration for national socialism; but he does famously write that he seeks to “transcend politics” through his art. During the German occupation of Norway, he did sometimes assume an accommodating stance toward the authorities–for instance, by allowing German soldiers and the Reich minister of culture to visit his studio and view his work (though he himself refused to receive them in person)–but this was because Vigeland, as a sculptor, was in possession of large quantities of bronze which he justifiably feared would be confiscated and shipped to the gun foundries of the Reich if he didn’t play ball. This would have put an abrupt end to his life’s work, the installation at Frogner Park (now known as the Vigeland Park.)

One also needs to understand Vigeland’s personality and character. He was indeed irascible, selfish, and myopic, like many other visionary artists. By the time Norway was invaded, Vigeland was in his seventies and lived like a hermit in his studio, working constantly and shunning almost all social contact. He can certainly be criticized for not taking a firmer stand against the authoritarianism of his age, but this must be weighed against the role of an artist in a situation of tyranny. Vigeland did what he felt was needed to defend his work and his vision–which is ultimately humanitarian and life-affirming–in the midst of war, political chaos, and social upheaval. That said, he never joined the NS (the German-backed national socialist party that ruled Norway during the occupation), or publicly endorsed their policies, unlike some of his contemporaries on the Norwegian art and culture scene.

When Vigeland died in 1943, Norway was still occupied by the Germans. His estranged son from his first marriage, Alf Gustav Vigeland Jr., had joined the NS, and, in an attempt to co-opt his father’s artistic legacy for the national socialist cause, arranged a large state-sponsored funeral in defiance of the elder Vigeland’s wishes for a small, private memorial service. This association of the Vigeland name with Nazism still persists in the public imagination and has unfortunately led many Norwegians to erroneously believe that Vigeland was either a Nazi or a Nazi sympathizer.

I am an American who has lived in Norway for almost 20 years. I am currently writing a book on Vigeland and have researched his life in depth.

As a surgeon and painter I have seen both sides. You seem to dwell upon the dark one…or at least not to understand a tempered two year old. P