Did you miss the first part of this post? You can catch up here.

Building the Tudor Dynasty, Part II: Lady Margaret Beaufort and the Years of Waiting Dangerously

So, um, it’s been a little while since I updated this series on Lady Margaret Beaufort and building of the Tudor dynasty. Need to catch up? Read Part I here.

Part II: The Years of Waiting Dangerously

I’m going to go out on a limb here and state that the years between 1471 and 1485 were the lowest of Lady Margaret Beaufort’s life. Not only was she separated from her son, with no idea of when or even if she would see him again, but the very claim to the throne that necessitated Henry Tudor’s exile looked increasingly irrelevant with each passing year. It had to be a curious and painful limbo for them both; too dangerous to be left to their own devices, but not formidable enough to take control of their own destinies.

The Perils of Widowhood

When Margaret sent her teenaged son out of England in 1471, following the defeat of the House of Lancaster in the Wars of the Roses, she probably breathed a great sigh of relief. Her son was now the senior male heir (however remote) of the defeated Lancastrian dynasty, and the victorious Yorkist king, Edward IV, was absolutely not going to risk a revival of the conflict.

Had Henry remained in England, the best he could expect would be an arranged marriage into some safely Yorkist family, perhaps even to one of King Edward’s younger daughters. This arrangement would effectively neutralize Henry’s claim and deprive him of the possibility of making a more advantageous marriage. (Of course, Henry did end up married to one of Edward’s daughters, and the match was anything but disadvantageous, but matters were very different when Edward was alive. Thing can change pretty quickly when a king dies).

Wax figures depicting the infancy of Henry Tudor, on display at his birthplace, Pembroke Castle, in Wales. The richly-attired woman in red is presumably Margaret, who looks both bummed out and way too old (Margaret was 13–yes, you read that right–when she gave birth). Maybe it’s meant to foreshadow the troubles to come. There is really no reason to include this picture, other than that I think it’s kind of awesome. But now we all know that Pembroke Castle is open to the public! {PD-Art Wikimedia Commons}

But Margaret’s own position wasn’t much better. While her sex did accord her a measure of protection (as it would twelve years later when she was caught dabbling in treason), a rich woman with royal blood was a special case. In an instance of spectacularly bad timing, Margaret’s second husband, Sir Henry Stafford, had died earlier that same year. With the Yorkist victory, this was not a good time to be an unmarried woman with known Lancastrian sympathies and Lancastrian blood. Though nobody seriously considered putting a woman on the throne, Margaret’s royal lineage was cause for alarm. Within months, she had married again, this time to Sir Thomas Stanley, later Earl of Derby, a famous political fence-sitter who had nonetheless managed to ingratiate himself with the Yorkists.

It is unclear precisely how Margaret’s third marriage came about. Nor do we know if she married under some degree of duress. Most studies represent Margaret as taking the initiative and making the best of a bad situation. This is plausible, because, short of entering a convent or joining her son in exile, there was simply no way she was going to be allowed to stay single.

Margaret’s unmarried status was no less a threat to the newly-reinstated Yorkist dynasty than was her son Henry with his thin royal blood. Actually, in 1471, with Yorkist power not yet consolidated, it may have been an even greater one. Henry was safely out of the way; Margaret was right there in England with royal blood in her veins and an immense fortune at her disposal.

This portrait has been in the possession of the National Portrait Gallery in London since at least the 1930s. The family with whom it originated had long associated it with Margaret Beaufort, but modern scholars agree that it is not her. The mistake may be due to the woman’s gabled hood and how her hands are folded in prayer, both of which recall Margaret as she was depicted in middle age.

I’ve included it partly because I think it is a reasonable reflection of what Margaret’s state of mind must have been throughout the 1470s and early 1480s. Famously devout, she certainly took comfort in her faith, but, in limbo and surrounded by enemies, she must occasionally have despaired. I also just think it’s a really beautiful portrait. I especially like the use of light and the detailed embroidery on the hood. So hats off to the artist, whoever you were. {Wikimedia Commons}

The crux of the issue was that whomever Margaret wed, would be, theoretically, in a position to appropriate her claim to the throne. There is a even plausible case to be made that the last Lancastrian king, Henry VI, had been thinking just this when he arranged Margaret’s first marriage, to Henry’s own half-brother, Edmund Tudor. There was also the problem of Margaret’s age. At not quite thirty, there was nothing stopping her from producing more Beaufort-blooded babies to jangle the Yorkists’ nerves. Lastly, she was a wealthy woman who could always, say, equip a small army, if she so chose.

But, of course, Margaret was as vulnerable as she was dangerous; the blood and wealth that made her a threat also made her a target Edward IV could not ignore. And so she married Stanley, less than a year after the death of her Stafford husband–a notably short period of mourning for a man of whom, by all accounts, she had been deeply fond. Her unseemly haste speaks to the urgency of the situation.

Margaret was shrewd enough to recognize that marrying somebody was in her immediate best interest. As long as she remained single, she ran the risk that Edward would pressure her into a far less satisfactory match. Choosing a Lancastrian (provided she could find a live one after the carnage of two decades of war) would have been like sending the king a handwritten note politely informing him of her intent to foment further rebellion.

It’s tempting to read into Margaret’s motives our own awareness of what was to come, but I doubt that Margaret chose the slippery Stanley because she foresaw his usefulness in putting her son on the throne. It is very unlikely that she was plotting much of anything at this stage. In the wake of the Lancastrian collapse, Margaret’s focus would have been on damage control, not rebellion and dynasty-building. At most, she was taking a “wait and see” position. But in the meantime, she had to make sure that her son was safe and that she herself remained at liberty.

Stanley had one last selling point: his high standing with King Edward ensured that he and his wife would be often at court. There Margaret could keep her eyes and ears open and even advocate for her son. All the same, it must have been an intensely difficult time. Whatever she thought of her new husband as a person, she certainly couldn’t trust him. Her high position at court was, in theory, an honor, but nobody had forgotten her Lancastrian connections and she was surrounded day and night by enemies. If being at court kept her abreast of the latest political news, it also meant that she could never let her mask slip.

Plots, counterplots, treasonous alliances, and failed rebellions

So if Margaret didn’t start plotting her son’s ascendance to the throne at the moment of the Lancastrian defeat, when did she start? It is impossible to be sure, but probably not for a considerable period of time. Within a few years of the Lancastrian collapse, the Yorkist dynasty was looking very secure. Edward IV had two sons and, failing them, brothers, nephews, and a host of daughters. More importantly, the king and his government were competent and popular. With each passing year of peace and renewed prosperity, interest in reviving the dynastic conflict faded.

Meanwhile, Henry Tudor remained in exile, officially the guest of the duke of Brittany, but in reality a hostage and diplomatic pawn–and one whose value fluctuated from year to year. With the seemingly vigorous Edward IV secure on the throne, the Bretons periodically considered handing Henry over in exchange for an English alliance. Margaret made at least one attempt in the early 1480s to negotiate a settlement with Edward that would at least allow Henry to return to England, but this came to nothing.

But in 1483 everything changed. In a rapid and stunningly dramatic series of events–the kind any good creative writing teacher insists students avoid lest they come across as absurd–Edward IV died unexpectedly and with no clearly-articulated plan for the minority rule of his twelve-year-old son, now King Edward V.

This series of portraits of various 14th, 15th, and 16th-century English monarchs, hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. The portraits feature several key players in Margaret’s story. On the top row, second from right, is Edward IV, with his son, the ill-fated Edward V, at his right. On the bottom left, is Richard III–for whom Margaret would cause several headaches–followed by Margaret’s beloved son, Henry Tudor. All pretty mediocre copies, they were likely made by the same artist and for a single patron.

This created a power vacuum and it was not clear which of the rival court factions would come out on top. But Edward’s surviving brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was not interested in playing political tug-of-war, and within weeks had pushed an act through Parliament declaring Edward IV’s sons illegitimate, and himself the rightful heir. On July 6th, he was crowned King Richard III. This dizzying turn of events came about in less than three months.

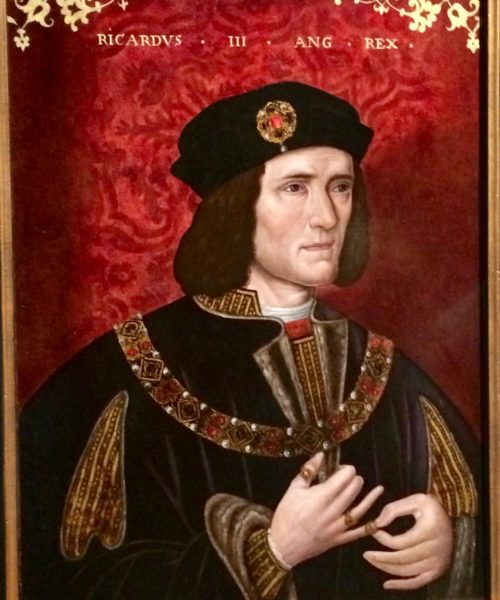

Richard III, Margaret’s nemesis between 1483 and 1485. Immortalized by Shakespeare as a wicked hunchback, Richard’s reputation has been fought over for five centuries. Interestingly, x-rays have shown that this portrait, a 16th century copy of a 15th century original, was altered at some point to emphasize that the right shoulder was higher than the left.

Richard’s actions split the Yorkists and so alienated other members of the ruling class that he almost immediately faced resistance. His situation worsened as his young nephews (the deposed Edward V and his little brother) disappeared from public view and rumors circulated that they were dead. (They probably were, and yes, probably on Richard’s orders.) In this political firestorm, Margaret saw her chance, but she needed an ally who could sway the discontented Yorkists to her side. She found one in Elizabeth Woodville.

Elizabeth Woodville was Edward IV’s widow, and the mother of his children–the same children who had just been declared illegitimate due to Richard’s machinations. Fearing for her own and her remaining children’s safety, she had fled to sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. Never a woman to pass the time with needlework, she immediately began plotting.

Margaret spent the next several months conspiring with Elizabeth, and all under the nose of the rather shrewd Richard. She sent various members of her household to Elizabeth, on the pretense of tending to her ill health and jagged nerves. Margaret proposed that her son Henry would marry Elizabeth Woodville’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York. By way of a dowry, young Elizabeth would shore up Henry’s chances by merging his claim with her own, much superior one, and bring with her the loyalties of the old Yorkist supporters.

[Total aside here, but it always strikes me as incredible that Richard did not keep closer tabs on Margaret, Elizabeth, and the people close to them. That the widowed and embittered Yorkist queen suddenly shared a physician with one of the last of the Lancastrians is something that you’d think would set off a few alarms. I think the explanation lies with the underdeveloped state apparatus of late medieval England. Monarchs were usually cash-strapped and, in any case, efficient, professional bureaucracies were still in their infancy. It would be another century before Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I’s spymaster, had the resources to organize the sixteenth-century equivalent of the secret police. So perhaps cleverness and discretion really were all that was necessary. This is worth remembering if you ever find yourself plotting to overthrow a medieval monarch.]

Events accelerated in the fall of 1483, when the Duke of Buckingham, Richard’s cousin and one-time supporter, raised a rebellion, seemingly out of the blue, against him. Margaret lost no time in throwing her considerable resources behind Buckingham, and summoned Henry, and whatever mercenaries he could raise, to join them.

Why would Margaret support a claimant other than her son? Most likely to use the ensuing chaos to create a window for Henry to come to England, claim the throne, and marry his Yorkist princess. She must have reckoned that getting rid of Richard was the top priority and that Buckingham could be dealt with later.

Some scholars have even suggested that, far from simply co-opting the rebellion, Margaret, who is known to have encountered Buckingham several weeks prior, egged him on and perhaps even put the idea in his mind. That is pure conjecture, but the motive behind Buckingham’s hare-brained, badly thought-out rebellion has never been clear. That he was manipulated by those with sharper wits and their own agendas is as plausible as any other theory I’ve come across.

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. He had supported Richard III’s usurpation of the throne, but then inexplicably turned against him. Margaret sought to take advantage of his rebellion; did she also instigate it? {Wikimedia Commons}

Buckingham’s rebellion quickly collapsed, so quickly, in fact, that Henry Tudor didn’t even have time to land in England. Delayed by bad weather, he reached the coast only to learn that the rebellion had already left the station–and had then promptly derailed. Figuring that the uncertainty of exile in Brittany was preferable to the certainty of a traitor’s death in England, Henry wisely hightailed it back to the continent.

“she had of late conspired, confederated, and committed treason“

Whether or not Margaret was actively involved in Buckingham’s rebellion, Henry Tudor had definitely been on his way to England with regime change on his mind, and nobody doubted Margaret’s involvement on that front. King Richard moved immediately against her. Parliament passed a statute declaring Margaret guilty of treason, stripping her of her vast wealth and titles, and essentially putting her under close house arrest. Her husband, the Yorkist Henry Stanley, was granted a life interest in her estates, but actual ownership was claimed by the crown.

As harsh as this sounds, Margaret got off easy. Had she been a man, she would certainly have been executed. Historians have long puzzled over Richard’s relative mildness. Certainly, it was meant, at least in part, to keep Stanley happy…but it wouldn’t be enough to keep him loyal. Stanley didn’t interfere with Margaret’s continued communications with Henry and may have actively assisted in their plotting. At some point he began to think of his stepson as a horse perhaps worth backing.

(For what it’s worth, I think Stanley made the decision to turn his coat sometime between April 1484–when Richard’s only legitimate child died–and March 1485–when his wife and queen died of tuberculosis. Widowed and with no heir, Richard would be expected to remarry–shaking up the game once again and bringing who-knew-what new players to the table.)

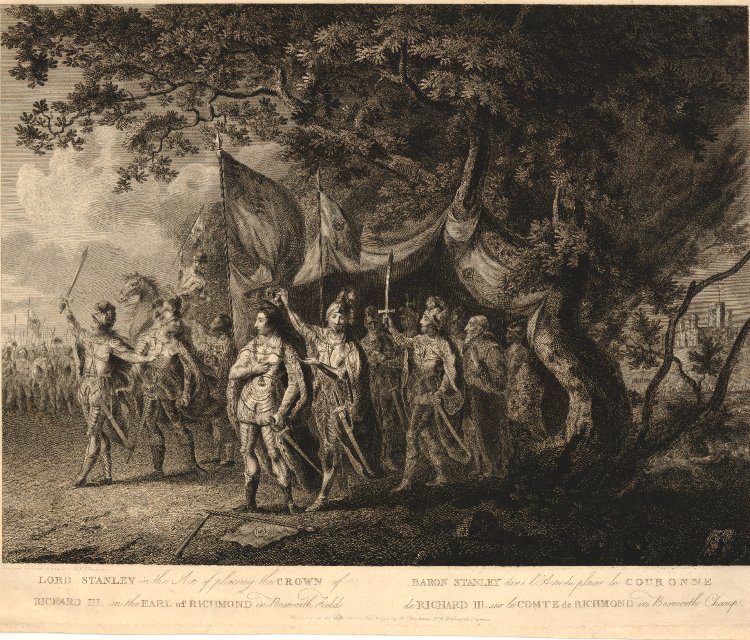

In years to come, enemies would slander Henry Tudor as a weakling dominated by his mother. But while he depended greatly on her counsel and support, Henry was perfectly capable of operating without her. Two years after the Buckingham fiasco, he would make another play for the throne, meeting Richard at the Battle of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. At the crucial moment, summoned to support Richard, Stanley held himself and his men aloof from the battle, giving Henry’s army its chance and ensuring its victory. In Richard III, Shakespeare even has Stanley placing Richard’s (literally) bloodied crown atop Henry’s head.

Coming up (soon, I promise!): Part III, “My Lady the King’s Mother.”

This Post Has 0 Comments